Demographic Shift Towards an Aging Population

With fertility rates declining, the demographic makeup of South India is shifting towards an aging population. A telling indicator of this is the old-age dependency ratio, which measures the number of elderly individuals (aged 60 and above) for every 100 people of working age (15 to 59 years). By 2036, South India is expected to have an old-age dependency ratio of 19.4, much higher than the projected 15.2 in Northern states.

This shift brings with it significant challenges. The region’s aging population is growing faster than that of other parts of India, potentially putting strain on public resources. As the proportion of working-age people shrinks, fewer individuals will be available to support a growing elderly population. This could burden healthcare systems and pension schemes, leading to calls for more social safety nets and healthcare services catering to older citizens.

Socio-Economic Impacts and Political Concerns

An aging population and reduced workforce also carry political ramifications. Southern states, traditionally more prosperous and with stronger infrastructure, could face reduced political representation in the future. As their population growth slows relative to Northern states, their influence in national affairs—particularly in Parliament—could diminish.

For South India, which has long been seen as an engine of economic growth, this demographic reality also affects future workforce availability and productivity. Fewer young people entering the job market could impact industries that rely on a steady stream of talent and labor, challenging the region’s economic resilience.

Future Projections and Policy Responses

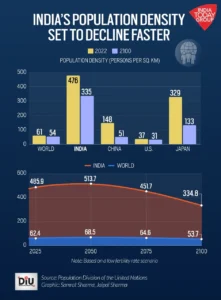

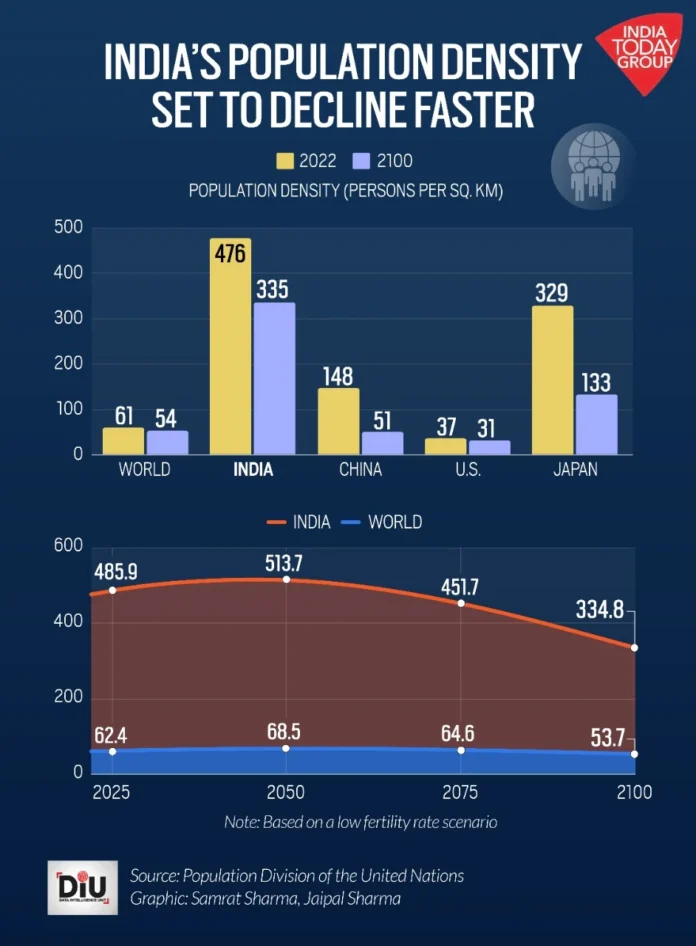

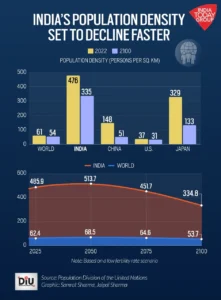

Looking ahead, the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) estimates that by 2050, around 20% of India’s population will be aged 60 and above. In South India, where the fertility decline began earlier, this trend is expected to be even more pronounced. By 2036, the elderly population in India is projected to grow from 10 crore in 2011 to around 23 crore.

In response to these demographic changes, leaders in the South are already considering pro-natalist policies. In Andhra Pradesh, the Chief Minister has floated the idea of incentives for families who have more children, recognizing that boosting birth rates is one possible solution to offset the declining young population.

As South India grapples with the consequences of its low fertility rates, policymakers will need to carefully navigate the economic and social shifts that come with an aging population. While incentives to encourage larger families may address some concerns, a more comprehensive approach—focused on healthcare, social services, and economic reform—will be essential for the region to maintain both its economic strength and political relevance in the years ahead.